The Qur'anic Christmas

I am no theologian, but like most Indian Muslim kids, I have learnt how to read the Qur’an in Arabic. My main teachers were my sister in Sydney and a ‘maulana’ (religious teacher) in Karachi.

The maulana had a very simple approach to teaching the Qur’an. Basically he had three sticks. One was long and thin, the use of which created a stinging sensation. The second was short and thick, to generate pain. The third was long and thick which he used as a walking stick to support his heavy-set frame.

I spent some six months learning to read the Qur’an in a small mosque school (known as a ‘madressa’) in Karachi. The mosque was called Jami al-Falah (where ‘Jami’ meant ‘place for congregational prayer’ and ‘al-Falah’ meant ‘divine felicity’).

It all sounds very exotic, doesn’t it? In fact, the mosque was named after the street it is located on — al-Falah Road.

Studying here didn’t bring much divine felicity. If anything, it brought lots of pain and misery to this seven year-old from Sydney.

My mother beseeched the maulana on my behalf: ‘Please, Maulana Sahib! My son is from Australia. He has very thin skin. Go soft on him.’

The maulana was characteristically fierce in his response. ‘Even if Bhutto sent his son to learn the Qur’an from me, I’d hit him and his father as well!’

Mum didn’t make similar submissions to my elder sister when assigning her the task of teaching me the Qur’an. My sister tended to make use of much softer wooden kitchen spoons, which would frequently break.

(And of course, what I am conveniently leaving out of the whole picture is the quite legitimate disciplinary concerns which made the use of such utensils necessary.)

At age 14, I was given my first translation of the Qur’an in English. It was a very old translation first published in Lahore in Pakistan during the 1930s. The translator was an Indian chap who rose to the highest posts in the Indian Civil Service that formed the administrative bedrock of the British Raj. His name was Abdullah Yusuf Ali, and his is perhaps the most popular and widely used translation.

I was 15 when I donated a copy of his translation to my school library. Some readers may not regard this event as all that significant; but mine was the first Qur’an to grace the shelves of the library of St Andrews Cathedral School, Sydney.

It was at school that I discovered the story of the Qur’anic Jesus. And since we are approaching Christmas, I would like to share that story with you using the translation of the late Mr Ali. I wish to apologise in advance to any readers who find the story too boringly familiar. I also apologise for the King James style language used by Ali.

The story can be found in a chapter of the Qur’an named ‘Maryam’ (which is Arabic for ‘Mary’). It begins with the usual supplication that commences all but one chapter of the Qur’an: ‘In the name of God, Most Gracious and Most Merciful’. This supplication is used not only when commencing a reading of the Qur’an, but precedes virtually all the daily actions of a Muslim, both mundane and devotional.

The chapter then goes into how John the Baptist appeared on the scene. John (named ’Yahiya’ in classical Arabic) was born to Zachariah, and both father and son are revered as prophets.

Once John has been mentioned, Mary is introduced. She is described as withdrawing from her family ‘to a place in the East’. She locks herself away from the rest of society, and yet a man mysteriously appears in her private chamber. The following dialogue ensues:

MARY: ‘I seek refuge from thee to God Most Gracious: come not near if thou dost fear God.’

MAN: ‘Nay, I am only a messenger from the Lord, to announce to thee the gift of a holy son.’

MARY: ‘How shall I have a son, seeing that no man has touched me, and I am not unchaste?’

MAN: ‘So it will be: Thy Lord saith: “that is easy for Me: and We wish to appoint him as a sign unto men and as a Mercy from Us”. It is a matter so decreed.’

The man, of course, was an angel. Christ was conceived miraculously. Once born, Mary took her son back to her family. Her father was a respected Rabbi and Mary was always known for her modesty and chastity. One can only imagine how embarrassed she must have felt when she came holding a baby in her arms.

Making things even more uncomfortable was that Mary had made a vow not to speak to any man for a fixed period of time. When she was first publicly accused of sexual impropriety, she pointed to the baby Jesus.

The Qur’an thus describes the first miracle of Christ — his speaking from the cradle in defence of his mother. His exact words were:

I am indeed a servant of God: He hath given me revelation and made me a prophet. And he hath made me blessed wheresoever I be, and hath enjoined on me prayer and charity as long as I live. He hath made me kind to my mother, and not overbearing or miserable. So peace is on me the day I was born, and the day I die, and the day I shall be raised up to life again!

I’m not sure if Joseph or the Three Wise Men appear in the Qur’anic account. But a number of his miracles are mentioned. These include healing lepers and restoring life to the dead. Also mentioned are the ascension of Christ, and the sayings of the Prophet make specific mention of Christ’s return to earth to establish the kingdom of God toward the end of time.

Each year, I celebrate Christmas with my best mate from school. He still sings for the St Andrews choir. Some years back, I introduced him to a Japanese friend of mine. They instantly clicked. I was best man at their wedding. It was a truly Australian event — an Anglican boy marrying a Buddhist girl with a Muslim best man and with all this taking place at St Andrews Cathedral!

And while I am celebrating Christmas, my Kiwi Muslim friend will be sorting a selection of books I mailed to her in time for Christmas. She never met her Muslim father, but her Catholic upbringing did little to contradict her Muslim heritage.

Christmas is a special time in many Muslim countries. The Palestinian West Bank town of Bayt Lahm (Bethlehem) plays host to thousands of pilgrims each year. In Pakistan, the government-owned TV stations play Christmas programs on Christmas eve. Christmas day is a public holiday in Pakistan and numerous other Muslim-majority States.

This year, Christmas falls almost exactly between the two large Islamic feast days of Eidul Fitri and Eidul Adha. Yet regardless of the timing of these feasts, which varies each year in accordance with a lunar calendar, Christmas is an inherently special occasion for believers of Jesus from all faiths.

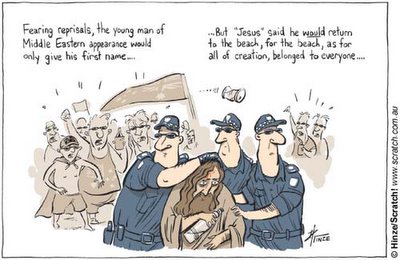

I’d like to think it isn’t just the Qur’anic nativity scene that unites Christians and Muslims. I hope that we can go beyond the paradigm of civilisational clash and recognise that, in essence, we have the same spiritual heritage. On that note, I’d like to wish everyone reading this all the very best for Christmas.

(First published in New Matilda on 21 December 2005)

0 comment(s):

Post a Comment

<< Home